Luckin Coffee engaged in one of the most brazen frauds in history. It is easy to blame the fraud on the business environment in China fostered by the CCP. But this fraud could not have occurred if not for systemic weaknesses in the Western capital markets.

After the Enron scandal, Sarbanes Oxley was passed to create stringent new standards that would deter future frauds. Auditors were supposed to play a key role in enforcing these new stringent standards. Publicly traded companies had to pay their independent auditors to offer an opinion on whether the internal controls of a company were effective (requiring the auditors to test management’s financial reporting).

In 2012, the Obama administration signed bipartisan legislation relieving some companies of the obligation to get this opinion from their auditors. This change lowered the costs associated with taking a company public, and eased access to capital for many businesses. The White House promised that this bill “will help encourage startups and support our nation’s small businesses.” (emphasis added) But this law did not just apply to American businesses, it applied to all businesses, including those in foreign countries.

Why is this a problem? If an American company takes advantage of the relaxed requirements and commits fraud, they take a significant risk that they will ultimately be exposed and go to jail or get sued. But when a well-connected company in an emerging market, like China, engages in fraud, there is no recourse for investors. It is even possible that some level of fraud is encouraged by the people in power.

Encouraging more investment in American businesses might be an important enough public policy goal to justify the increased risk of fraud that comes with loosening standards, but there is no such public policy justification for loosening standards for companies in emerging markets with structurally weak regulatory systems.

Congress Lowered Standards in 2012

Congress wanted to increase economic growth by easing access to capital markets for companies that are were often considered too small to take public. To create this ease of access, they created a new category of company, called an Emerging Growth Company (EGC) in the JOBS Act in 2012. Generally, an EGC is one that has less than a billion dollars in revenue and less than $700 million in equity. If a company remains under the revenue threshold, it can keep its EGC status for up to five years.

An EGC is only required to provide two years of audited statements (instead of three), and less extensive disclosure on executive compensation, and it can delay compliance with new accounting standards. But perhaps the biggest advantage of EGC status is an exemption from receiving a SOX 404(b) opinion, where the independent auditor attests that management’s “internal controls” over financial reporting are effective.

The “internal controls” are the first line of defense against fraud and human error. Management is supposed to install a system that aids employees in routinely recording the economic activity of the company in a way that is both accurate and comprehensible. The controls should also ensure that neither employees nor management misuses company assets or manipulates results.

Management has an inherent interest in creating effective internal controls over its employees, but not necessarily for itself. In fact, management often has a conflict of interest. The Enron scandal is just one example of how management can easily succumb to the temptation to manipulate results. Policymakers created the SOX 404(b) attestation requirement so that independent auditors would look over the shoulders of management and help ensure that management’s internal controls were effective.

The cost for a SOX 404(b) opinion varies, but it can exceed $2 million a year, especially at the early stages of implementation. The high cost is due to the independent auditor testing and evaluating the internal controls on financial reporting throughout the year, a time consuming and expensive process (although likely much lower in a labor market like China). This extensive year-round testing makes concealing a large-scale fraud far more difficult for management. Luckin’s auditor Ernst & Young Hua Ming LLP uncoverd the fraud, and would have probably have detected the inflated revenues and costs even earlier if it had been testing the internal controls throughout the year. However, Luckin was classified as an EGC, and therefore, EYHM did not offer an opinion on their internal controls and did not do the requisite testing:

“The Company is not required to have, nor were we engaged to perform, an audit of its internal control over financial reporting. As part of our audits we are required to obtain an understanding of internal control over financial reporting but not for the purpose of expressing an opinion on the effectiveness of the Company’s internal control over financial reporting. Accordingly, we express no such opinion.”

The SOX 404(b) Attestation Has a Real Impact on the Quality of Internal Controls

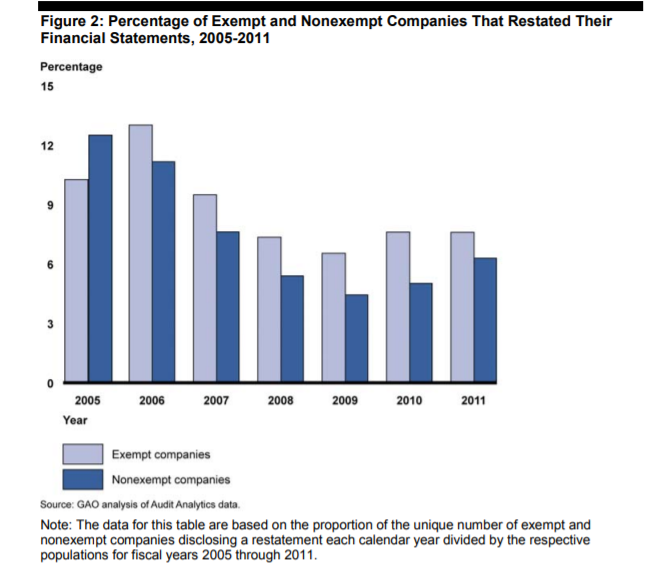

Even though SOX was passed with the idea that it would cover every company, implementation for small issuers (those with less than $75 million in market cap) were initially given an exemption, and eventually permanently exempted by the Dodd Frank Act in 2010. An investigation was done by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) in 2012 to see if the SOX 404(b) requirement had any effect on the quality of internal controls. The GAO studied restatement rates between companies that had met the SOX 404(b) requirement (either by law or voluntarily) and those that did not; the results indicated that companies without the SOX 404(b) requirement had weaker controls and therefore filed more restatements.

This indicates that the SOX 404(b) attestation requirement improves the quality of the internal controls at a company. In its conclusion the GAO report (which used data provided by Audit Analytics) concluded that the SOX 404(b) attestation “may be useful for investors in gauging the reliability of a company’s financial reporting.”

By permitting EGCs an exemption to the SOX 404(b) attestation, Congress may have unintentionally lowered the quality of internal controls. Luckin is just one particularly bad example. Consider it this way, if a company makes a big splash with an IPO, and the company is too big to be considered a “small” issuer (with less than $75 million in market cap), then it probably needs extra scrutiny, not less. Instead EGCs get a pass. We are troubled about the implications of EGC status in the West. But we are positively alarmed by the implications of EGC status in Chinese companies, where real enforcement is effectively impossible.

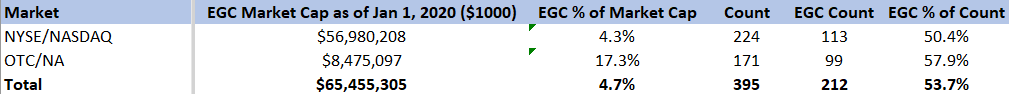

Luckin took advantage of its EGC status to forego a SOX 404(b) auditor attestation, but they are not alone. Our analysts compared all Chinese companies trading on the Nadsaq, NYSE, and OTC exchanges:

Our analysts determined that 53% of listed Chinese companies listed on the Nasdaq, NYSE, and OTC exchanges were classified as EGCs. The collective market cap for these companies is over $65 billion. This may only represent a little less than 5% of the total value of all Chinese based companies traded on U.S. exchanges, but it is still a significant sum.

Conclusion

Some people have been quick to blame the auditors Ernst & Young Hua Ming LLP for not uncovering this fraud earlier. But can people really blame EYHM when it was Congress who loosened the restrictions so that EYHM would not vigorously test and evaluate the internal controls at Luckin? (The issues surrounding EY in this story are very complex and we will give them their own treatment another time).

EGCs essentially have no oversight until the auditor arrives to conduct the year-end audit. That means the current bill passed by the Senate that would delist companies whose auditors are not subject to inspection by the PCAOB, would not have stopped the fraud at Luckin, even if the CCP acquiesced to inspections by the regulator. As it stands now, foreign companies in emerging markets that are considered EGCs have a one-year period where they can fabricate numbers before the auditors come to check their books.

Public policy makers should be concerned that other foreign companies like Luckin may attempt to use EGC status to run short term scams on the capital markets. It would be a good step to insist that every company from an emerging market meet the SOX 404(b) requirement before listing.

Contact us:

Retail Investors get free access to our Watchdog Reports. Institutional Investors and those interested in our Gray Swan Event Factor can subscribe, or call our subscription manager, at 239-240-9284.

If you have questions about this blog send John Cheffers, our Director of Research, an email at jcheffers@watchdogresearch.com. For press inquiries or general questions about Watchdog Research, Inc., please contact our President, Brian Lawe at blawe@watchdogresearch.com.