Restatements have become less common, but other methods of correcting prior periods have increased.

The Roots and Consequences of Corporate Financial Restatements

Financial restatements, i.e., restatements for violations of U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP), fall into several categories. The most serious “Big-R” or reissuance restatements address material errors that call for the reissuance of a past financial statement. The “little-r” revision restatements are intended to deal with immaterial misstatements, or adjustments made in the normal course of business. A third, even milder form of correction is the out-of-period adjustment (OOPA), used when an error is corrected within the current period but the change is deemed immaterial to both the current and prior period(s).

Financial restatements usually signify that a company isn’t doing well; although sometimes, as in the recent spate of restatements by SPACs, they represent a response to a regulatory change, in this case the SEC’s requirement to reclassify warrants. Even when there is no evidence of fraud, Big-R restatements, little-r revisions, or even OOPAs may be indicators of systemic management problems. Here we examine some of the scholarly literature from the past two decades or so to find the roots and indeed the consequences of corporate restatements.

Rise and Fall

Writing in 2008, Susan Scholz described the enormous increase in restatements starting 20 years ago, from 90 in 1997 to 1,577 in 2006. Restatement frequencies begin to accelerate in 2001, before the passage of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX).

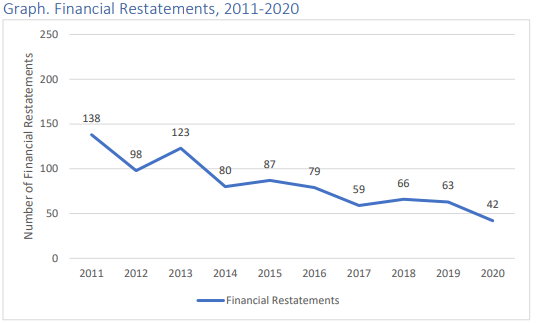

However, the number peaked in 2006, and has been falling ever since, to a 19-year low of 484 in 2019, according to Audit Analytics. That number includes little-r revision restatements, which comprised over 80% of all restatements in 2019; that year there were just 63 Big-R restatements. Of the 2019 restatements, 57% had no impact on income statements. The number fell further in 2020, with only 42 Big-R restatements, representing 0.8% of companies:

Source: Watchdog Research’s “2020: Frequency and Impact of Restatements” by Burke and Yarbrough. (available on request)

The number of OOPAs also rose while restatements fell, with the most referenced adjustment issue in OOPAs being taxes.

Not Just Sloppy

Restating companies are typically unprofitable even before the restatement. Even when there is no apparent fraud, restatements often show evidence of preceding underlying meaningful earnings management. Future fraud occurrences are positively correlated with restatements due to negligence, and with the severity of restatements.

Bad News for Those at the Top

Among the least surprising findings is that CEOs’, CFOs’, directors’, and audit committee members’ careers all decline after restatement, with some exiting voluntarily and others being shown the door. Conversely, firms whose CEOs and CFOs have more experience make fewer restatements.

Auditors are also likely to resign or be replaced after restatements, though this is less common for Big Four accounting firms. Again, firms employing auditors with more experience, or even having audit committees with greater financial experience, undergo fewer restatements.

Clawbacks Create Perverse Incentives

Clawback provisions allow companies to reclaim some portion of executive compensation after restatements that show worse performance. Clawbacks are meant to deter misreporting. However, there is a higher likelihood of auditor dismissals after Big-R reissuance restatements when firms have clawback provisions in place, a “shoot the messenger” type of reaction. But if the firm with clawbacks only issues a little-r revision, the auditors are less likely to be dismissed, giving the appearance of quid-pro-quo cooperation.

Thus, clawback policies may create perverse incentives for managers to replace uncooperative and independent auditors who insist on a restatement with more compliant ones, who might try to skirt the issue with a mere revision. The effect of clawback provisions is stronger when the CEO earns higher incentive compensation, suggesting that auditor dismissals are more about the effects on managers’ careers than about concern for the firm.

Firms with clawback provisions are also more likely to have more OOPAs, including firms with previous restatements and future restatements. This also indicates management may be opportunistically using lesser corrections such as OOPAs to avoid pay deductions that would occur if there were a restatement.

First, the Bad News About Little-r Revisions

Many times, little-r revisions are used when* *Big-R reissuance restatements should have been used. Rachel Thompson found that almost 40% of revisions meet at least one materiality criterion, and therefore should have been restatements. She reports that firms conceal material misstatements by reporting revisions rather than restatements, especially when it affects compensation. However, the market is not fooled in the long run and punishes revising firms with material misstatements, but with a lag time.

Managers behave opportunistically by manipulating earnings to stay within the revision limits. But when auditors require auditees to make financial restatements, management opportunism may potentially decrease.

Now, the Good News About Little-r Revisions

As compared to Big-R restating firms, little-r revising firms are generally more profitable, less complex, and show some evidence of stronger corporate governance and higher audit quality. Little-r firms have lower free cash flows, higher board expertise, higher CFO tenure, are less likely to use a specialist auditor, and are less likely to have material weaknesses in their internal controls than either restating or even non-revising firms.

Greater purchases of non-audit services (NAS) shortens the length of the adjustment period, decreases the number of OOPAs, and lessens the likelihood of a revision restatement.

Badertscher & Burks note that the SEC recommends more use of catch-up revision adjustments rather than restatements to correct accounting errors. They found that lengthy lags, which were considered a possible detrimental outcome of this policy, are uncommon, and appear to be largely unavoidable consequences of fraud investigation. The proposed reforms would have a negligible effect on disclosure timeliness.

The Market Speaks

The average market reaction to restatement announcements is negative, with a more pronounced negative market reaction to more transparent negative effect restatements than the positive reaction to more transparent positive effect restatements. In other words, bad news causes more of a market downturn than good news causes a market upturn.

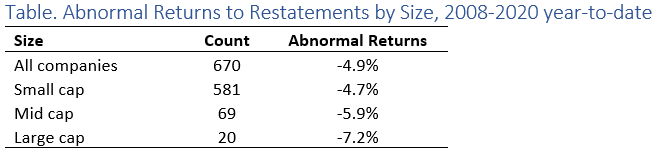

Although small-cap companies are five times more likely to issue a restatement than large-cap companies, the drop in share price is worse for the latter.

Source: Watchdog Research’s “2020: Frequency and Impact of Restatements” by Burke and Yarbrough. (available on request)

However, beginning in 2001, the magnitude of market reactions declined notably, coinciding with the increase in restatements between 2001 and 2006. Hirschey et al. attributed this more subdued market response to restatement announcements to effects of SOX. Firms also responded to the legislation; those incurring a negative market reaction in the year following restatement announcements reported their financial statements more conservatively post-SOX.

Restatements attributed to fraud and those affecting revenues tend to have more negative market reactions. However, the percentages of restatements due to fraud declined from 29% of 1997 restatements, to under 1% in 2014. The proportion of restatements explained by clerical errors also fell from over 14% in 2008 to about 1% in 2014, with the remaining 98% explained by accounting errors. These reductions in fraud and clerical error have been attributed to increased regulation, technology, and education.

How can Firms Avoid Restatements?

What reduces the need for restatements? As noted above, having more experienced officers and auditors coincides with lower rates of restatement. Audit effort is also negatively correlated with restatement. Better employment practices reduce both internal control ineffectiveness and the need for financial restatements. Time pressure appears to be a factor increasing the probability of financial restatements, so perhaps allowing more time for the initial statements could reduce the incidence of restatements.

Conclusion

Restatements of every kind, but particularly the more serious Big-R reissuance restatements, have declined dramatically in the last fifteen years, as have restatements due to fraud or clerical error. It is not entirely clear why. One explanation is that financial reporting has improved, another plausible explanation is that firms are reclassifying restatements as revisions and out-of-period adjustments to lessen the impact of the correction on the company, its auditors, and its executives.

It is clear that the careers of executives and auditors involved with restatements suffer. Although recommended by the SEC because of its timeliness, a little-r revision or an OOPA may be used to cover up material misstatements, especially when executive compensation depends on an absence of Big-R restatements. The market still falls after a negative restatement, but not as strongly as in the pre-SOX years.

If you are interested in our report on Restatements, or are just interested in learning more about our team, please contact jcheffers@watchdogresearch.com.