With the coronavirus shutting down entire industries and raising the possibility of an extended recession, pending mergers are in peril, and mergers overall will become disfavored as companies lose their appetite for risk.

BorgWarner and Delphi announced an all-stock merger on January 28th, 2020. The conventional wisdom take on this merger was that it was meant to protect to both engine auto part manufacturers from changes in the industry due to the rise of Tesla and electric vehicles. It would appear the BorgWarner was looking to absorb Delphi so it could use the increase in volume to protect its position in the market, not because Delphi performance made it particularly desirable.

BorgWarner placed the value of Delphi at $3.3 billion, quite a premium for a company whose stock price had been on a consistent decline for years, and had a particularly rough year in 2019, with a anemic $141 million in operating income and total equity of only $450 million. Naturally, lawsuits were filed against both companies when the merger was announced, but lawsuits are always filed when a merger like this is announced.

Delphi’s value has been on a steady decline since the summer of 2018

Delphi’s value has been on a steady decline since the summer of 2018

Why the Deal Fell Apart

On March 30th, Delphi announced that it was going to draw down its entire $500 million revolving credit so that it would have the cash on hand to endure the coronavirus and the accompanying government ordered shutdown.

The next day, BorgWarner announced that Delphi was in material breach of their agreement and that Delphi had 30 days to cure the breach or the merger would be scrapped. Delphi countered that BorgWarner had unreasonably withheld consent for the withdrawal. Both arguments have merit, so the stage is set for a nasty legal fight if the deal is not salvaged.

BorgWarner’s ostensible reason for backing out is pretty cut and dry. BorgWarner was not anticipating taking out new debt with its all stock deal. Delphi’s financial condition was anemic, but it was still in the black, and $500 million in potential new debt would be a hard to swallow (especially since it exceeds Delphi’s equity). But considering that the coronavirus pandemic will be relatively short-lived—it is expected to peak in mid-April—it seems strange that BorgWarner would insist that Delphi risk running out of cash and going bankrupt to keep the deal alive, when it had access to credit that would probably see it safely through the storm.

Instead BorgWarner gave Delphi two bad options, damned if you do, and damned if you don’t. Which leads us to believe that BorgWarner had soured on the whole idea of merging and used this credit draw down as a pretext to kill the deal.

Mergers Traditionally a Sign of Optimism

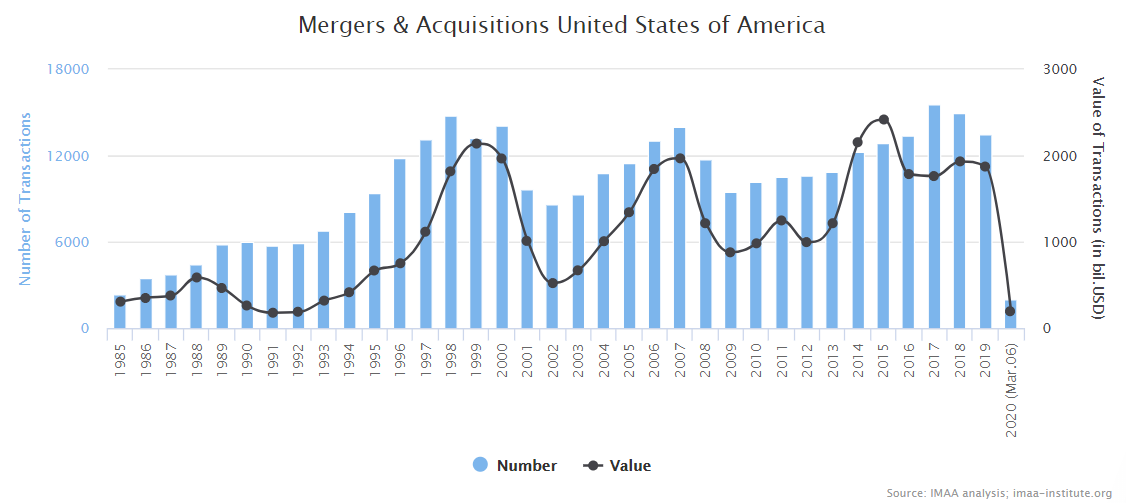

Mergers are widely considered a sign of optimism in the market, and the numbers bear that out.

This chart from the Institute of Mergers, Acquisitions and Alliances (IMAA) shows that mergers fell after the Dot-com bubble burst in 2001 and the housing bubble burst in 2008.

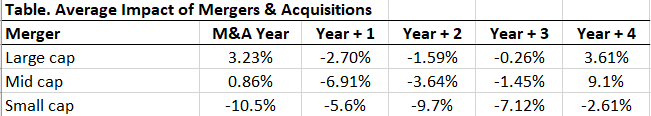

Mergers fell during these prior periods of uncertainty because almost all the benefits from a merger are long term. Our research shows that mergers generally produce negative returns for at least two years:

What accounts for these terrible numbers? Oftentimes the acquiring company must provide a large amount of cash to consummate the merger, which can leave the survivor strapped for cash or highly leveraged. In addition, there are often personnel issues, as established norms at one or both companies are upended, and egos are bruised. Additionally, the survivor usually inherits hidden accounting problems, and this can lead to write-offs, revisions, disclosure controls, or other gray swan events that damage the value and integrity of the company. This is why a recent merger will significantly increase a company’s gray swan event factor.

Positive outcomes depend on things like synergy, expanded volume, supply efficiency, and innovative technology or intellectual property (acquisitions to get new drugs in the pipeline is a feature of the pharmaceutical industry). These benefits are generally medium to long-term benefits.

If you look at the chart again you can see large cap companies suffer less than small or medium companies after a merger or acquisition, and that is likely due to the fact that big companies often acquire companies that are so much smaller than themselves, that it is completely irrelevant if the benefits of the merger materialize. PayPal for example, acquired TIO networks, only to essentially write off the entire value of the acquisition when they learned all the customer lists were compromised by a data breach, yet their share price did not suffer. Medium and small firms simply don’t have the luxury of having a merger turn into a complete boondoggle without paying a price.

We specialize in analyzing the risk of gray swan events, and the likely impact of those events on the future stock price. A merger is one of the biggest red flags that the acquiring company can have for gray swan events. Our research in this area affirms the conventional wisdom that generally depresses the stock price of an acquiring company because in the short-term, it is not a good bet.

In the current market downturn, companies do not want to double down on potential losses by adding a merger to the mix. Mergers in general are down. And it appears that companies have already inked mergers are looking through the fine print for a material adverse effect clause to bail them out. BorgWarner was probably thrilled when Delphi asked permission to draw down on their revolving credit, since it gave them a far more clear-cut excuse to bail on the contract than on an untested legal justification.

Suitors become Adversaries

Delphi’s stock sank as a result of this news. Generally, our gray swan event factor only penalizes the acquiring company once a merger is announced, not the acquiree. That is because generally the company that survives the deal is taking all the risk. But in an environment like this one, conventional wisdom has been turned on its head, and companies that have been counting on a merger are the ones in trouble.

What is important in an economic downturn like this is a company’s fundamentals. Delphi is a weak company: it had anemic financial statements when the market was strong, and problems at the helm to boot. Now, instead of wooing Delphi with a premium offer, BorgWarner has rejected Delphi in hopes that Delphi stumbles into bankruptcy so that they can get what they want at rock bottom prices.

Welcome to a new market, where fundamental analysis matters and cash is king.

Contact us:

If you want to subscribe to Watchdog Reports, call our subscription manager, at 239-240-9284.

If you have questions about this blog, send our content manager John Cheffers an email at jcheffers@watchdogresearch.com.